UNFPA Somalia Behaviour Change Communication and Family Planning Analyst Abdisalam Bahwal, based in the Garowe office, narrates a story of a fistula survivour, Farhiya, who trekked for three days across borders in pursuit of a life changing health service.

I met Farhiya during my recent visit to Garowe General Hospital in Puntland. At the time, Farhiya was preparing to check out of the hospital after two weeks of recovery following a successful obstetric fistula repair procedure. She consented to share her story with me and told me that she had lived with obstetric fistula, a debilitating condition, for seven years.

Farhiya is a 23-year-old Somali woman who received free fistula repair services together with 65 other girls and women, during a campaign at Garowe Hospital in Puntland carried out by Physicians Across Continents (PAC) in coordination with the Ministry of Health. UNFPA Somalia provided technical and financial support towards the campaign.

Farhiya is a living testimony to some of the root causes of obstetric fistula; early marriage and early pregnancy, which usually culminate into obstructed and prolonged labour. She was married off at the age of 15 in a village on the Ethiopian side of the border between Ethiopia and Somalia. She became pregnant at the age of 16. There was no skilled birth attendant in the village to assist her when she went into labour so she remained in prolonged labour for four days.

“Because there was no proper transportation, I was carried on a donkey cart to the nearest health centre in Kelafo district, tens of kilometers away from my village,” Farhiya explained.

At the health center, she was told that her baby had died. A midwife performed assisted delivery to remove the dead baby.

“My feeling of relief after sleepless days of exhausting labour was mixed with the sorrow of losing my baby,” Farhiya told me, adding: “I went back home and did not notice that anything else was wrong until a few days later when I discovered that I could not control my bladder. I returned to the health centre and was told that I had suffered from a condition known as obstetric fistula because of the prolonged labour. It was my first time to hear of such a medical condition.”

Personnel at the heath centre in Kelafo could not provide any remedy to Farhiya’s condition. She was told that there were no fistula experts in the area. “I returned to my village hoping that time will heal my body. After waiting for nine months with no improvement, I decided to cross the border into Somalia to seek medical care in Galkaio. I had heard of the presence of a doctor specialised in treating fistula. In one month, I was operated on twice without any success,” explained Farhiya.

Disappointed and depressed, Farhiya returned home and demanded divorce from her husband. “I was feeling guilty that my husband had to put up with my condition. I was also unable to bear any more children,” she said, adding: “my husband rejected my demand stating that he was willing to be with me despite my condition since he had married me healthy.”

She said she continued to stay in her village suffering in silence and living in isolation for six more years. “I used to hide from people and did not socialise with my neighbours. I kept the pain to myself. Only a few of my close family members knew about what I was going through,” she added.

In what she described as one of her few moments of joy in the many years she lived with the devastating condition, Farhiya received a telephone call from her aunt, who lives in Garowe on the evening of August 23. She was informed that some international doctors had arrived at Garowe General Hospital provide fistula repair services.

“My aunt told me that the doctors were only staying for a few days and she encouraged me to rush to Garowe Hospital. I talked the matter over with my husband, who agreed that I could travel to see if the doctors could help me. He gave me some money and sent me off to Gode district,” said Farhiya.

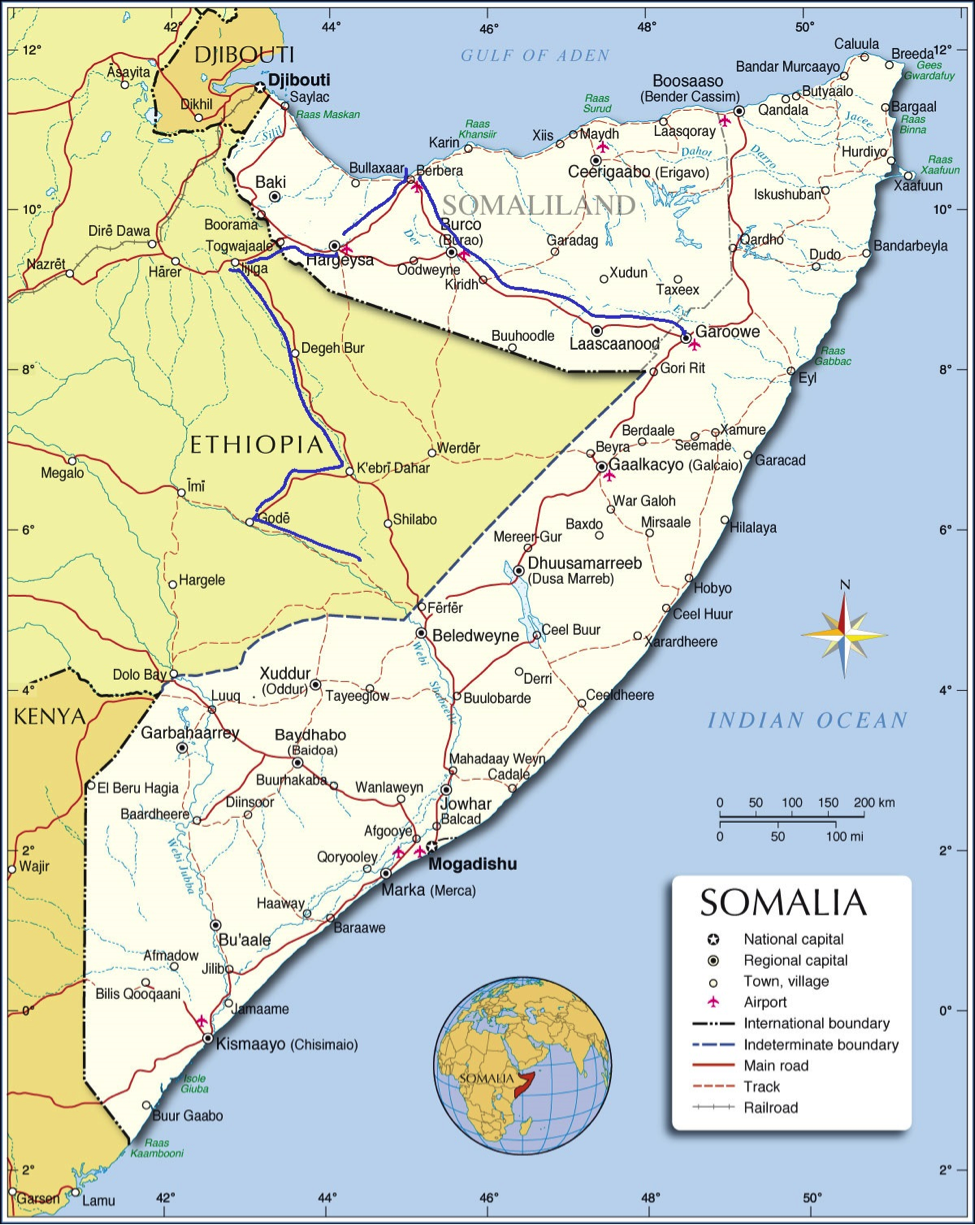

Due to the poor road conditions and the instability in some parts of the regions between her home and Garowe in northeast of Somalia, Farhiya had to take a longer and indirect route. First, she travelled north by road to Jigjiga, the capital of the Somali region of Ethiopia, where she spent a night. She then proceeded to Wajale on the border between Somalia and Ethiopia.

“I travelled further east to Hargeisa and spent the second night there. The next morning, in the final portion of my journey, I embarked on a day long trip to Garowe, arriving at midnight on Friday, August 26,” explained Farhiya.

In total, Farhiya covered more than 1500 kilometers in three days. She changed buses five times.

“I stepped into the hospital early Saturday morning on the last day of the five-day long campaign. I was the last patient the team of experts operated on. I am healed and I am now living normally for the first time in seven years. I must say that I am very happy,” said Farhiya.

The blue line on the map shows the distance Farhiya covered to access fistula repair services

Obstetric fistula is one of the most serious and tragic childbirth injuries. It is a hole between the birth canal and bladder or rectum caused by prolonged, obstructed labour, without access to timely, high-quality medical treatment. It leaves women leaking urine, faeces or both, and often leads to chronic medical problems, depression, social isolation and deepening poverty.

More than 2 million women in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, the Arab region, and Latin America and the Caribbean are estimated to be living with fistula, and some 50,000 to 100,000 new cases develop annually. Yet it is almost entirely preventable. Its persistence is a sign of global inequality and an indication that health systems are failing to protect the health and human rights of the poorest and most vulnerable women and girls.

As the leader of Campaign to End Fistula, UNFPA provides strategic vision, medical supplies, training and funds for fistula prevention, treatment and social reintegration programmes. UNFPA also strengthens reproductive health and emergency obstetric services to prevent fistula from occurring in the first place.

-----------------------------------------------------------

For more information please contact UNFPA Somalia Communications Specialist Pilirani Semu-Banda on e-mail: semu-banda@unfpa.org